Single-Path Code (1)

Single-path code, or branchless code, has been an important development in performance computing. The hardware acceleration features of modern processors are optimized for code without branches. The smooth flow of pre-fetching instructions to cache and pre-fetching their arguments to registers is disrupted by branches. Good compilers try hard to generate fewer branches, especially as you request that optimization is more focused on speed. In addition, the way that you write your source code can have a big impact on the number of executed branches.

In a series of three short articles, I will explain

- why branchless code is also important in embedded software, especially in hard real-time systems,

- how compilers can generate code with fewer branches from your unchanged source code, and

- how source code in a high-level language can be constructed to minimize branches, and some of the side-effects of such changes.

In this first article, let us look at some reasons why branchless code is so important. First, consider secure, encryption code, where different paths give rise to different timing and different power signatures. These can weaken the security in unintended ways, making branchless code extremely desirable, possibly essential.

Branchless code for encryption is the most extreme case, where we really need the code to contain no branches at all. In most performance computing, it is more the case that code with fewer branches beats code with more branches. So we are not necessarily talking about pure, branchless code, but rather small fragments that can be made branchless.

Modern, performance CPUs are good at executing instructions fast. So fast, that processors struggle to fetch those instructions from memory fast enough. All too often, the powerful CPU is left idle, waiting for the next instruction to be fetched. Decades of evolution by brilliant processor designers have brought a variety of ways to fetch instructions ever faster. Two key techniques are

- instruction cache (small, fast memory that can duplicate code store for faster access), and

- wide memory accesses (fetching more than one instruction at a time using a wide data bus and burst accesses).

Imagine we have an Arm Cortex-M processor preparing to execute a 16-bit Thumb2 instruction. Rather than fetching 16 bits from the code store, the processor might fetch 256 bits and place the extra code in instruction cache. With careful design, there need be no additional delay to the fetching of the 16-bit instruction, compared with fetching it direct from the code store. In the event that this instruction is not a jump, and the CPU simply wants the next instruction, it is already in cache and can be fetched with little or no overhead. However, if it is a jump outside of the fetched 256 bits, the CPU has to wait for a fetch from the main code store, a cache miss.

The difference between executing code that has been pre-fetched to cache and a cache miss is so great that CPUs have branch prediction facilities to try to pre-fetch also the destination of a branch instruction. This becomes more difficult when the branch is a conditional branch. How can the CPU know which way the control will flow until it fully executes all the instructions? Branch prediction for conditional branches can be done using hardware counters (to remember which branches were executed on the previous iteration of a loop) and/or with software hints. But it cannot be perfect and branch prediction failures occur, and have a measurable impact on software performance.

Even when a branch is correctly predicted, it will not always be the last instruction in a line of 256 bits, leaving some instructions pre-fetched but not needed. And the destination instruction will not always be the first instruction in a line of 256 bits, again causing some instructions to be pre-fetched and not needed. This effect makes poorer use of the cache, requiring more cache lines for a given number of executed instructions.

It is not simply the case that all branches are bad, and that branchless code is always faster. But if we can use a similar number of instructions, and do a similar number of data accesses, then code with fewer branches will be faster than code with more branches.

As well as being generally faster, code with fewer branches has more stable execution time than code with more branches. Even when we do not need perfectly constant execution time for cryptography, more stable execution time can be very helpful in a hard real-time system. Large variations in timing behavior can be difficult to accommodate in a predictable schedule. More stable timing is easier to understand, easier to model, and easier to test.

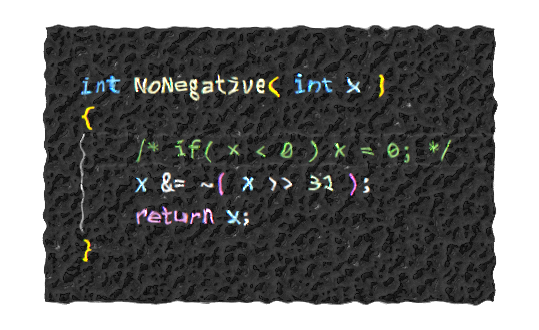

In the next article, I will demonstrate some compiler features that generate branchless object code from high-level C source code that contains if-statements that we normally associate with conditional branches.